A CONTEXTUAL CONSENT TOOLKIT

Purpose

The purpose of this toolkit is to provide a concise overview of the Contextual Consent Framework, offering practical examples of its application for various audiences including communities, individuals, tech leaders and executives, tech practitioners and regulators.

Intended Audience

There are many different intended audiences for this toolkit. The first intended audience is individuals and communities who need or want tools to be able to advocate for their autonomy, privacy, security and decision making in digital spaces or in situations where technology plays a role in the interaction. Examples of such situations include: facial recognition technology, recording or surveillance technology, deployment of generative AI or Artificial Intelligence Agents in different contexts and the use of robotics.

The second intended audience is industry leaders who are directly involved in technological initiatives, technical innovation efforts and modernization. People who fill roles or who work under the offices of Chief Innovation Officer, Chief Technology Officer, Chief Privacy Officer or anyone involved in Ethics, Responsible Technology and Compliance is a desired audience for this toolkit.

The third intended audience is for engineers and designers and anyone else who is directly involved in the design and deployment of consent flows within different socio-technical interactions.

Terminology

The following are key terms that we use extensively when discussing the Re-Imagining Consent in Technology Project and within this toolkit. Many of these terms are commonly used, while others are new definitions that we have proposed as part of our project. Though there may be multiple definitions for the terms below, I have only included the primary definition we are using to ground our thinking and our project.

Consent: an effective communication of an intentional transfer of rights and obligations between parties.

Contextual Consent: grounded in Helen Nissenbaum’s Contextual Integrity framework which proposes inferring user consent based on social norms for data sharing. Contextual Consent is a proposed definition that refers to a new way of thinking about consent flows in human-technical and socio-technical interactions based on a number of different factors discussed in this toolkit.

Socio-Technical Interactions: The ongoing interplay and interdependence between the social subsystem (people, culture, norms, expectations and values) and the technical subsystem (digital technology, networks, applications and data) within a given life domain context. Socio-technical interactions involve individuals interacting with (a) technologies, and (b) other individuals.

Human-Technical Interactions: The study and practice of how humans interact with a wide range of digital technologies that are intricately woven into our daily lives

Socio-Technical Design: Socio-technical design is concerned with advocacy of the direct participation of end-users in the information system design process. The system includes the network of users, developers, information technology at hand, and the environments in which the system will be used and supported.

Socio-Technical Agency: A new proposed term to describe the capacity for human groups within socio-technical systems to make decisions, or exert influence on their environment in ways that enable trust. Example: community dialog and platforms that can be used to inform/secure high impact consent engagements.

Life-Domain: the different, distinct areas of life that make up an individual's daily existence. For the purposes of our project we have defined and explored the following life domains: Family + Relationships, Health + Physical Wellbeing, Work + Career, Learning + Education, Recreation + Leisure, Spirituality, Community and Personal Identity.

Values: principles that guide a person's behavior and judgments, acting as criteria for what is considered good or bad

Norms: shared, unwritten rule or standard of behavior that is widely accepted, approved of, and enforced by a group or society

Expectations: A belief or assumption about what will or should happen, or what someone will do, in a specific situation.

The Contextual Consent Framework

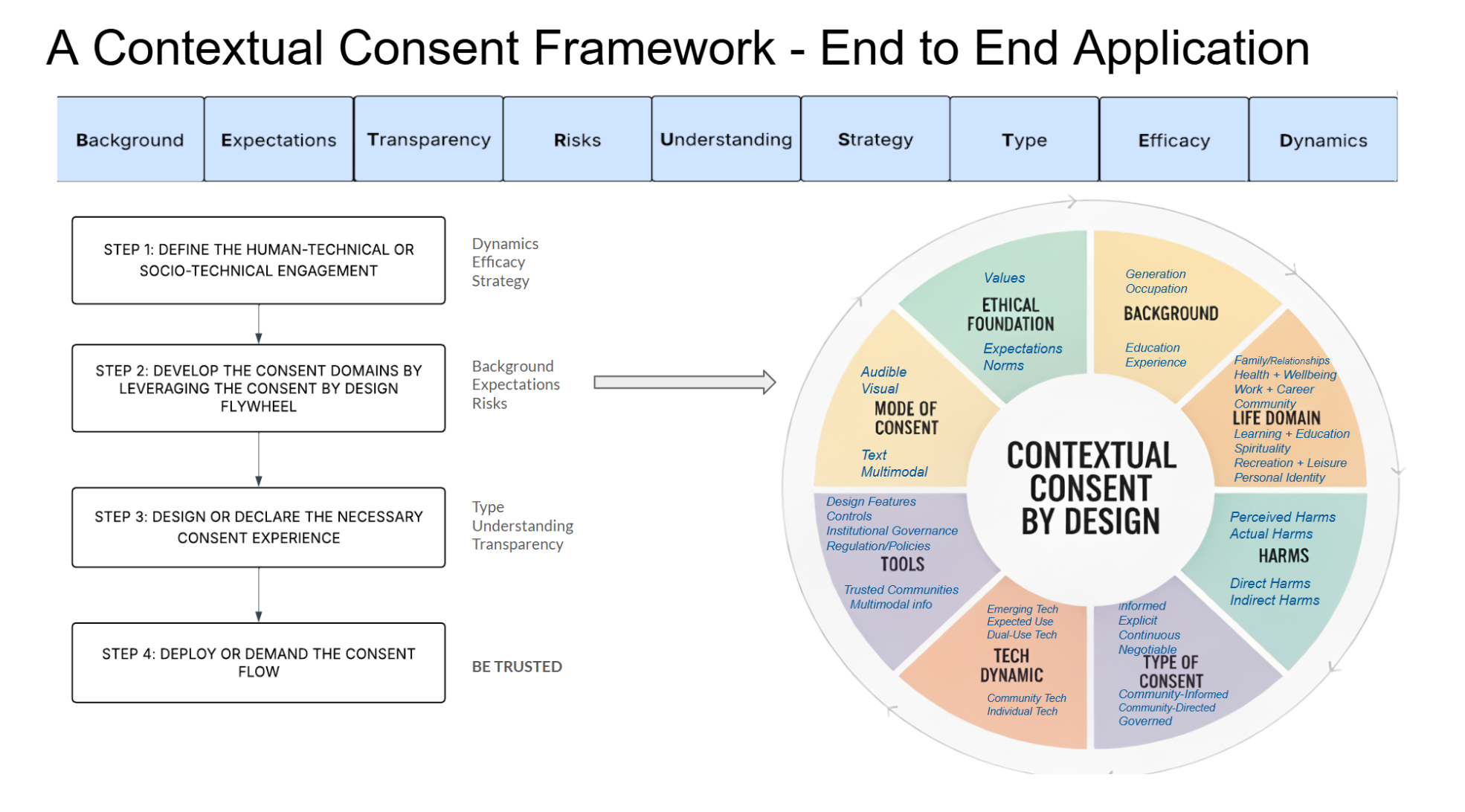

The Contextual Consent Framework consists of a set of principles to consider when designing consent flows into human-technical and socio-technical interactions; the four steps that enable the operational application of these principles in practice and a flywheel that defines the key domains of contextual consent.

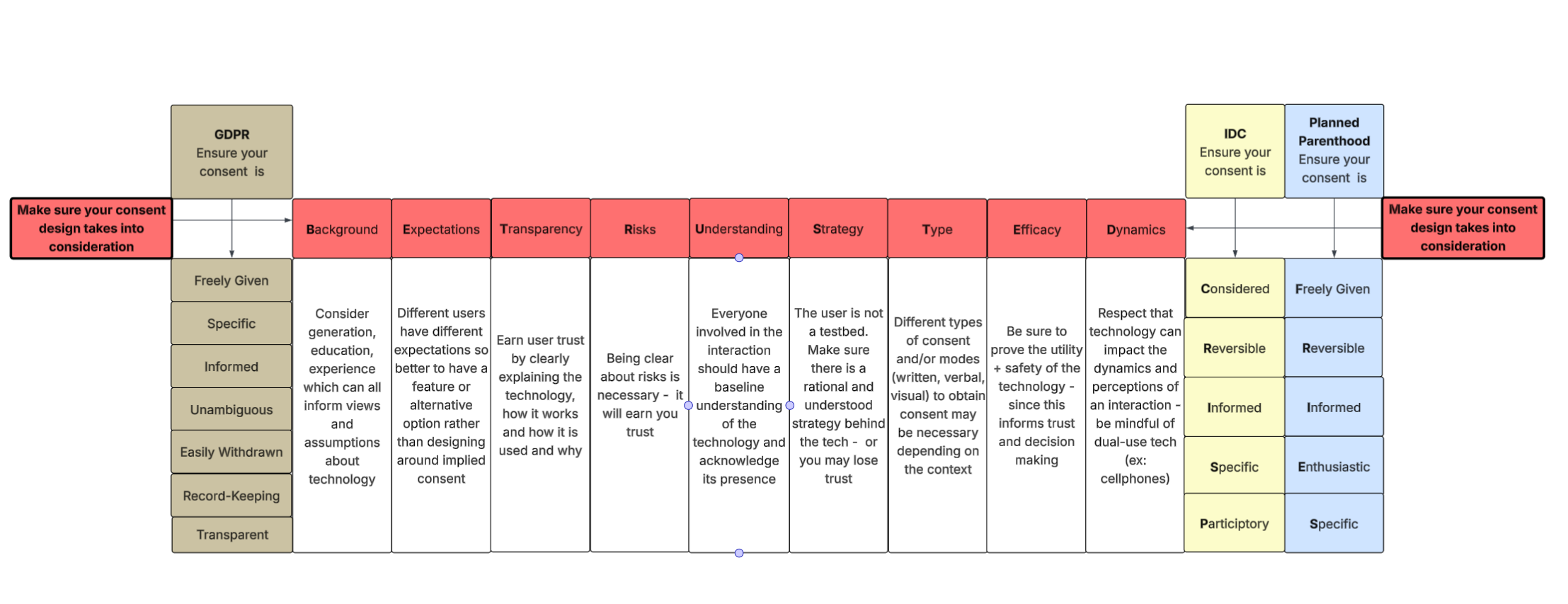

The proposed principles of contextual consent are: background, expectations, transparency, risks, understanding, strategy, type, efficacy and dynamics which collectively create the acronym BE TRUSTED. Each of these principles is an essential consideration that can inform the appropriate consent flow for whatever interaction you need to address. These principles complement existing consent requirement principles such as Planned Parenthood’s FRIES or the proposed CRISP model by providing a guide to what needs to be considered in order to ensure your consent flow meets such requirements. Below is a visual representation of how the BE TRUSTED principles can complement both FRIES and CRISP as well as European Regulation (GDPR in this case):

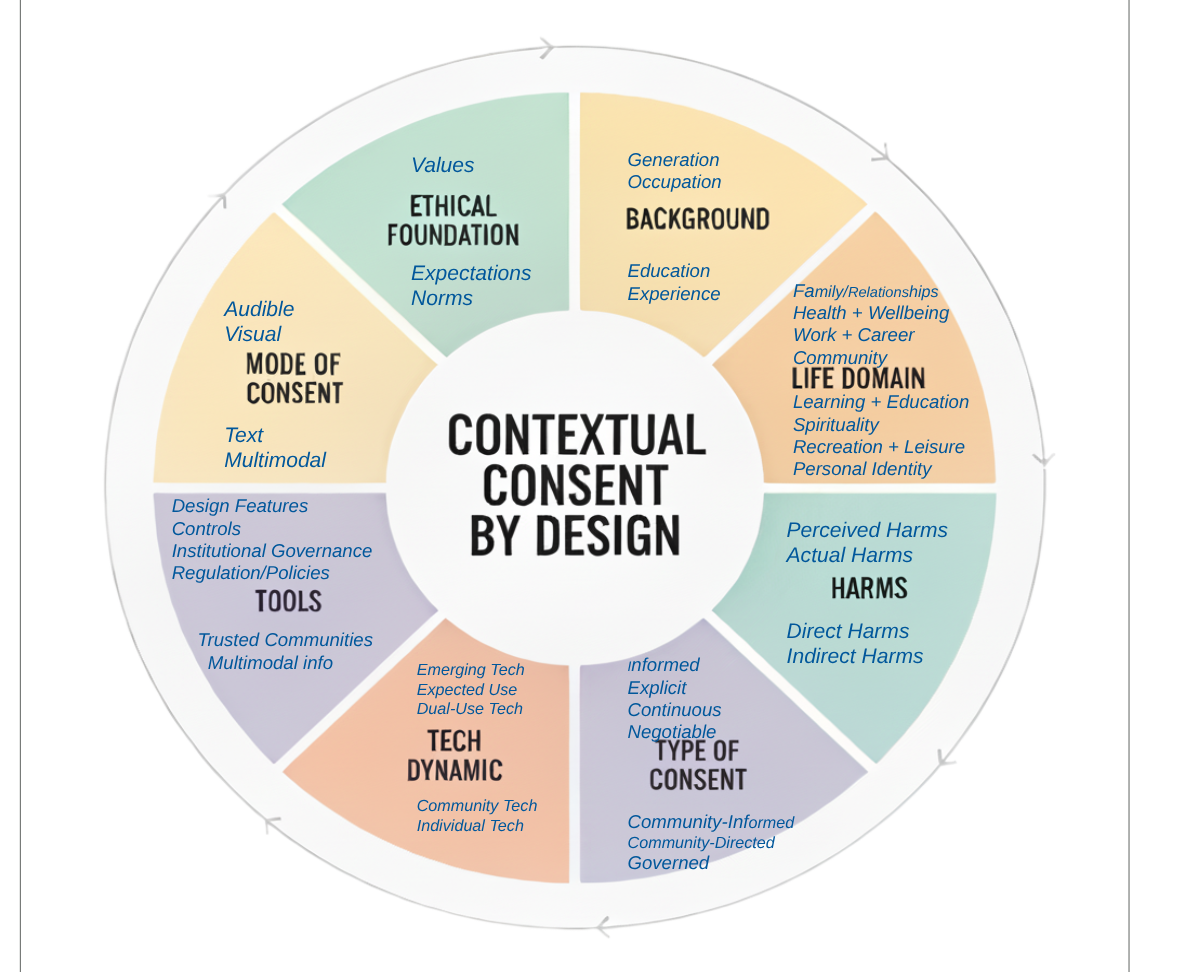

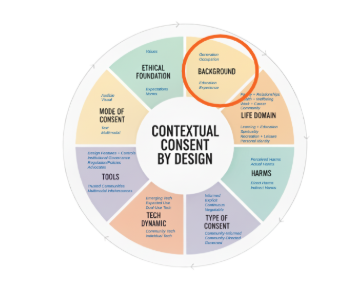

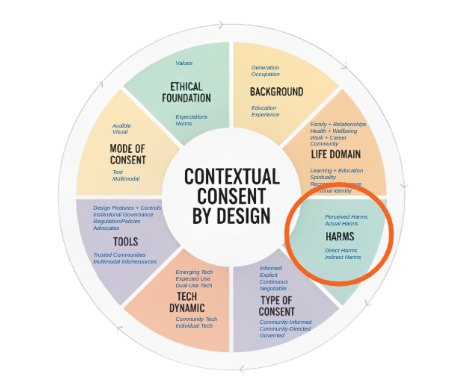

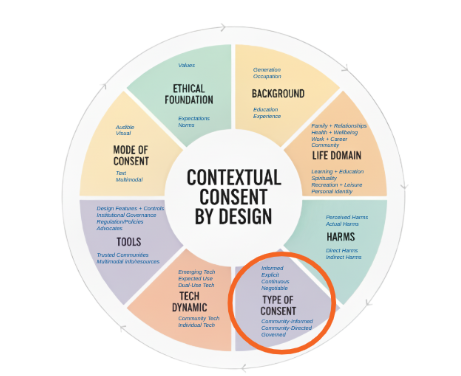

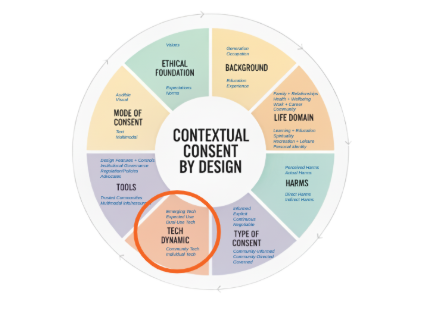

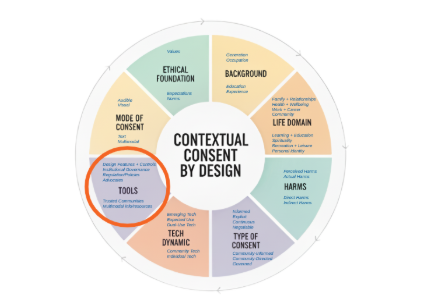

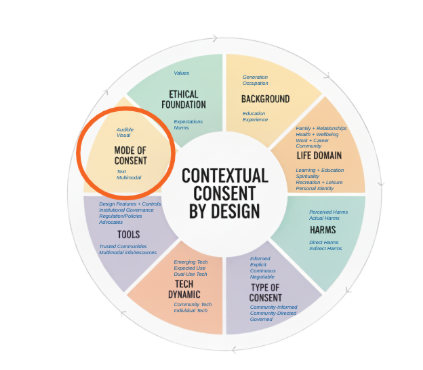

The Contextual Consent by Design Flywheel

The Contextual Consent by Design Flywheel is a tool to help individuals, communities and industry leaders understand and systematically cover the key domains that support a strong consent flow design.

To have a truly meaningful consent flow we recommend covering all eight domains however, in cases where time or resources preclude users from running through the entire wheel, even covering a subset of the domains will likely result in a more meaningful consent flow.

There are eight domains within the flywheel: Ethical Foundations; Background, Life Domain, Harms, Type of Consent, Mode of Consent, Tech Dynamic and Tools. Some of these domains are also principles but not all of the principles are components of the flywheel. The flywheel is intended to be a tool to consult as an input for the ultimate design or declaration of the necessary consent flow (step 3 in our framework).

Ethical Foundations

The Ethical Foundations Domain consists of the underlying values, expectations and norms that are present within the human-technical or socio-technical interaction. Often there may be contradictory values, expectations and norms present which may introduce friction in the engagement. This friction is important to acknowledge and deconstruct.

In our interviews as part of the Re-Imagining Consent in Tech Project, when we shared a hypothetical scenario with participants, we asked what values were important to them to uphold and also what values might be at play in the situation. In situations such as an AI Shopping Agent, participants noted the most important values being privacy, security and fiscal discipline but acknowledged some potential counter values on the part of the Agent deployer such as income generation, efficiency and innovation. In such cases where values differ between parties involved in the interaction, that is likely an indication that you require more types of consent in your design as well as more tools to enable equity in the interaction.

The same holds true for expectations and norms - in cases where norms are being challenged in the engagement then there is a higher chance you will need a more mature consent design. In our project, one example of a scenario where norms were challenged was in the case of grief bots being developed of the participant after their death. This scenario engendered a lot of thought and many participants were concerned about the unprecedented norms that might be set if their consent was not properly recorded.

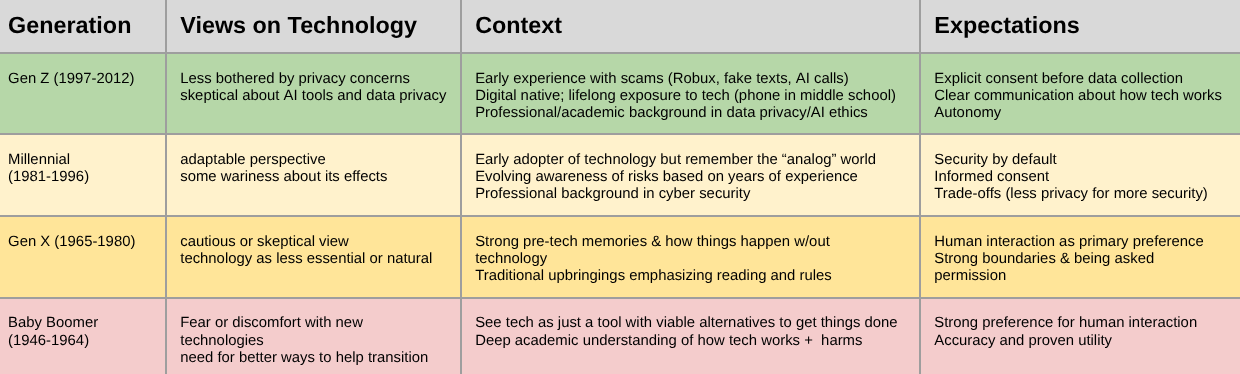

Background

Background is another important domain to consider. Based on our interviews and workshops, we found that people’s generation and professional background can have an impact on their general views on technology. This can in turn have an impact on their baseline assumptions and expectations about the technology being used within a socio-technical or human-technical interaction. Below is a snapshot of some of the themes that emerged from our project, specifically focused on generation.

From this chart you can see that younger generations, at least from our project insights, seemed to have less general concerns with technology but more focused and tool or domain specific concerns whereas older generations tended to have a broader general discomfort with technology in certain cases and a need for proven utility of the technology in order to feel comfortable.

Life Domain

Life Domain also adds additional context to how to approach consent design. In our project, we asked our participants to list their top 3 life domains that they consider most important out of a total of 11 choices. The top 3 most important life domains were Family + Relationships, Health + Physical Wellbeing and Work + Career. Though much more research and exploration is warranted to determine if this has a direct impact on specific consent criteria it is helpful to understand where people and communities may have more visceral reactions to insufficient consent flows based on the life domains they consider most important. One example might be social robots, which in a health + physical wellbeing context we found garnered some visceral reactions, one participant saying “I would punch that robot thing in the robot head every &x$!* day." whereas in a Recreation + Leisure context a social robot may warrant a completely different reaction.

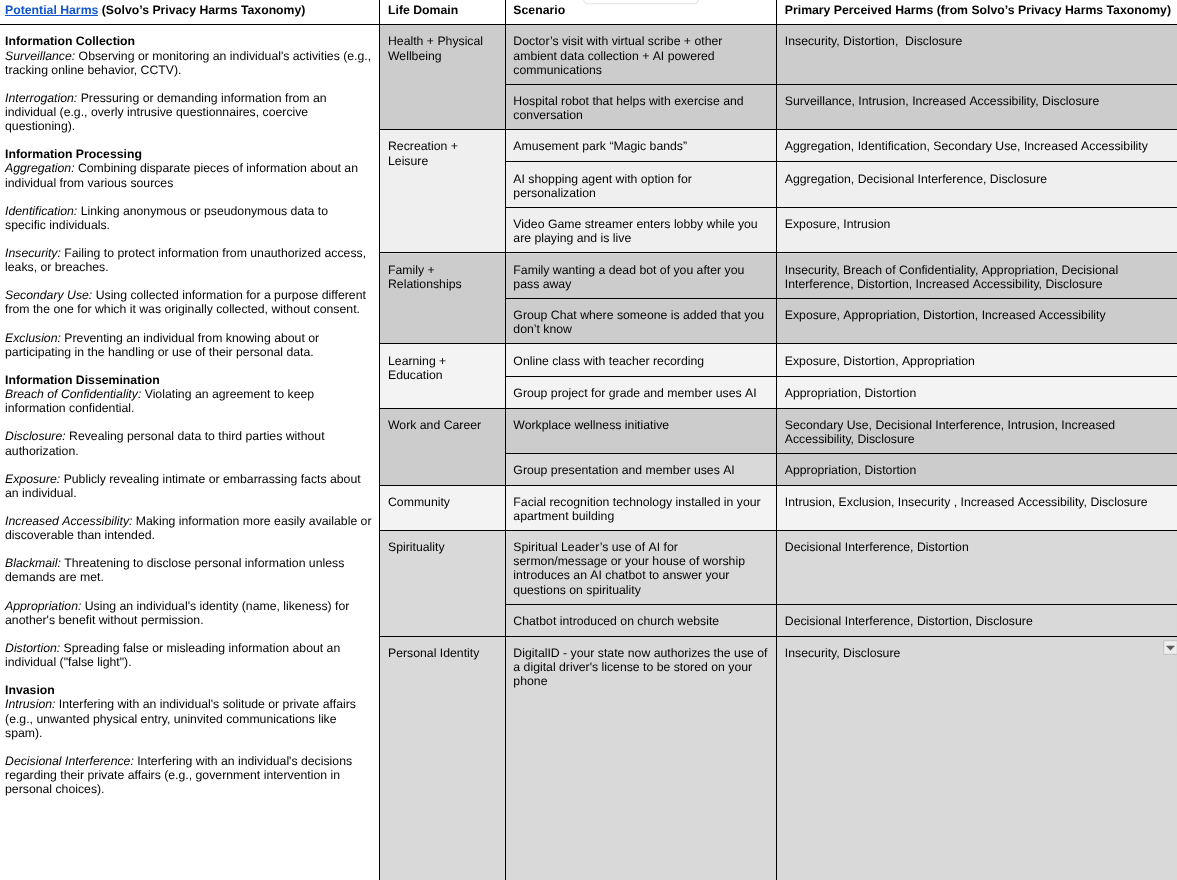

Harms

Harms are an incredibly important domain for contextual consent, specifically the perceived harms of those involved in the socio-technical interaction. Harms go hand-in-hand with the tools domain since the types of tools you need should be tied to the harms (either real or perceived) that you are trying to mitigate. There are many different types of harms that can manifest themselves in different ways.

As part of our project we referenced Daniel Solvo’s Taxonomy of Privacy Harms to understand and categorize the perceived harms that people shared for each of the scenarios, though in some cases we found that perceived harms extended into the physical realm, such as the social robot scenario and even the existential “what does it mean to be human” realm in the grief-bot scenarios Neither of these types of harm have a sufficient mapping with Solvo’s taxonomy given that it is focused primarily on data privacy.

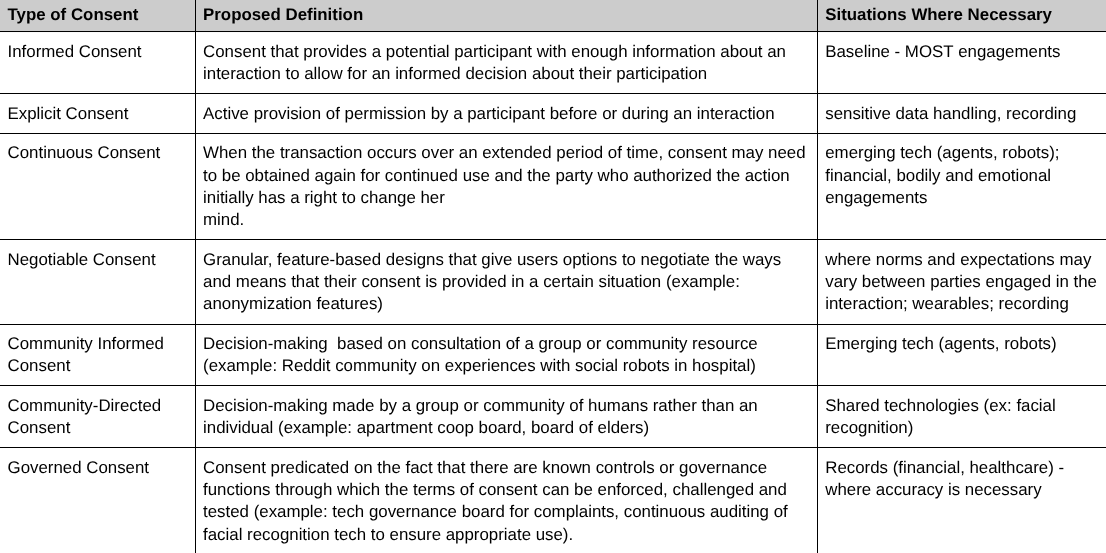

Type of Consent

Type of Consent is a domain that is informed by other domains. Depending on the context of the socio-technical interaction, it may be necessary to consider multiple types of consent. During the literature review phase of our project, we discovered that there are over 30 types of consent ranging from ubiquitous consent to coercive consent and everywhere in between.

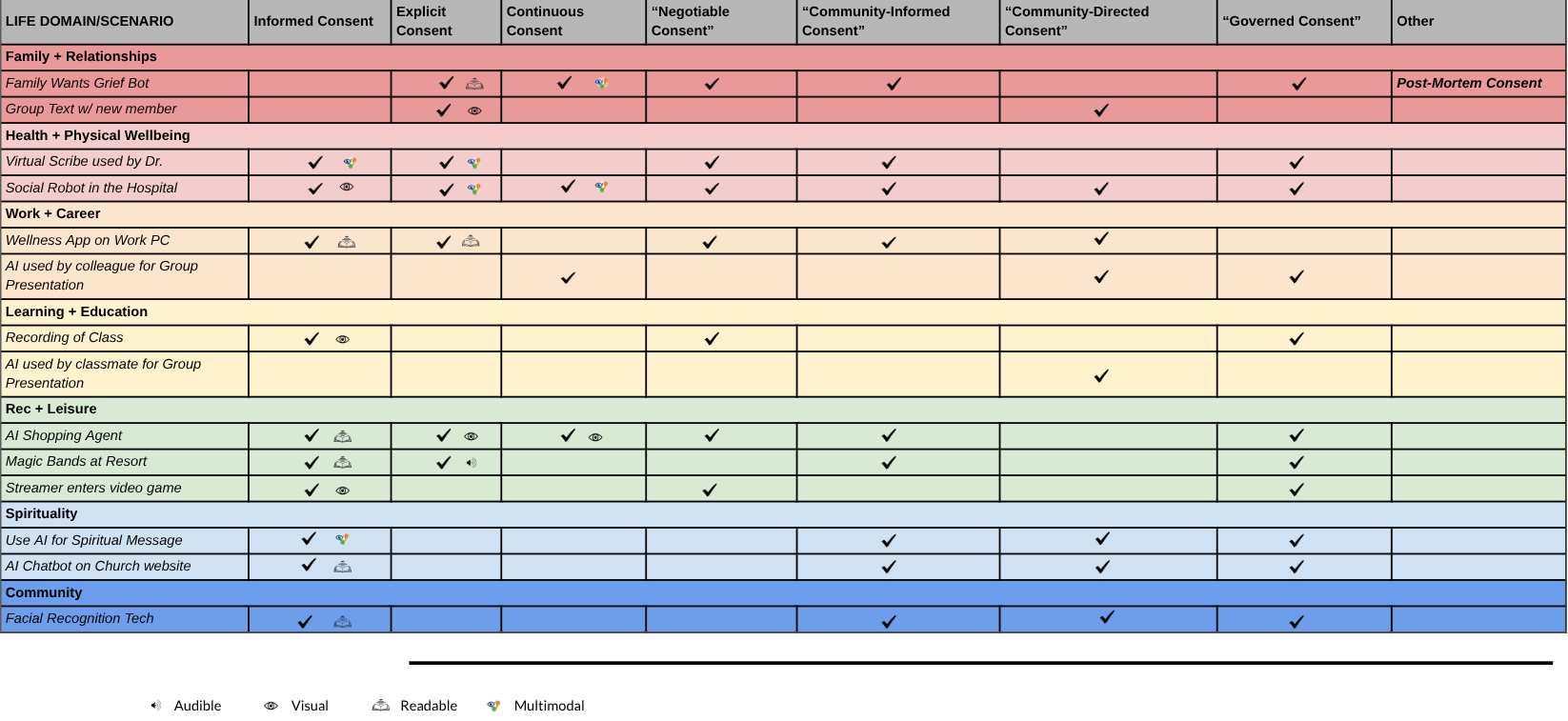

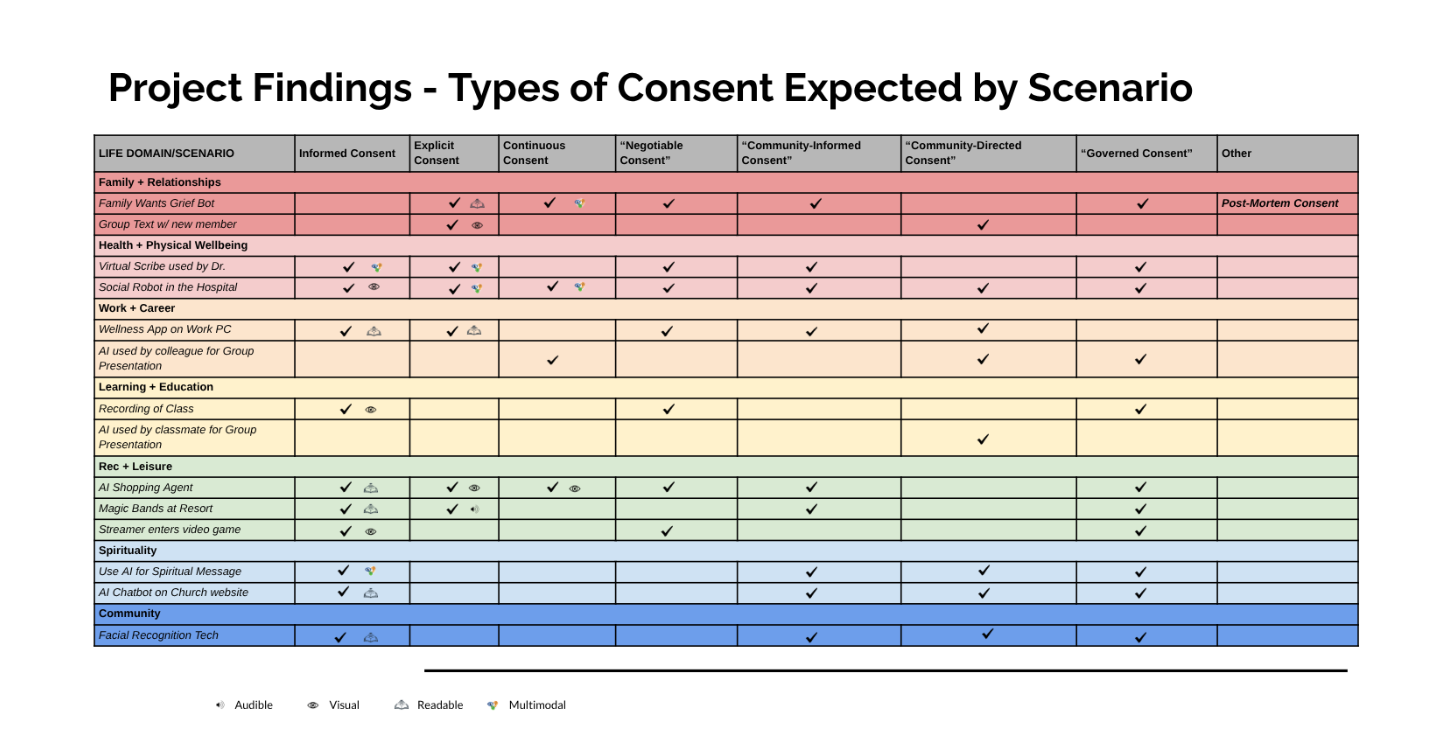

It is common to see socio-technical interactions where informed consent is the default, but we found through our interviews and workshops that there were many other forms of consent that participants desired and expected. We introduced a few more types of consent into our consent taxonomy based on the outcomes of our discussions. Below is a snapshot of some of the types of consent our participants noted during our project.

Additionally based on our discussions the following seemed to be some general guidelines for when certain types of consent were desired in certain situations:

Tech Dynamic

Another critical consideration for applying consent within socio-technical interactions is the acknowledgement of the impact the actual technology (whether it be the physical device at play or preexisting assumptions about the technology medium or intention) has on the engagement.

In our project we found that the types of technology, whether it be a cellphone or a robotic device can have profound impacts on people’s perceived harms even if such harms have a low chance of being manifested. One example was the use of a cellphone to transcribe a conversation during a doctor’s visit. In this case we found that people expressed concerns about the cellphone being a personal device and expressed a strong desire to have a device that looked medical in nature and was clearly intended for that specific use case to mitigate perceived harms of data being shared or exploited. In the case of robotics and agents, these were generally seen as more novel, emerging types of technology and our participants acknowledged wariness as to how these emerging technologies functioned and the importance of continuous consent to ensure values and expectations were being respected.

Furthermore, whether the technology used in the engagement primarily affects an individual or a collective also introduces distinct consent considerations. Interactions with a highly individualized impact (e.g., a doctor's visit or a digital ID check) contrast with those that impact a broader group (e.g., facial recognition in an apartment building or a chatbot used by a church). Our project findings reveal that when the technology's impacts are dispersed across a group, participants express a strong preference for collective forms of consent and prioritize group decision-making over traditional individual models.

Tools

The tools section of the flywheel is arguably the most substantial and impactful element of contextual consent considerations that if provided the necessary level of focus can transform your consent flow to better serve the humans it is intended to serve. By considering tools - you are distilling the key takeaways from the other sections of the flywheel to understand how to leverage those findings to build or ensure the necessary tools are in place to make your consent design effective. These tools can range from specific design features all the way through external governance processes or regulatory advocacy.

Through our project we found that features alone were not sufficient to completely alleviate perceived harms of technology within an interaction and that often there was a desire to know a higher level of regulation or certification were in place (such as in the facial recognition technology scenario) in order to feel comfortable. Another example of more extended, non-technical or feature oriented tools that people expressed a desire for was in the class recording scenario where the existence of an academic governance board to uphold values and expectation for technology was desired to ensure one’s terms for consent were sufficiently protected.

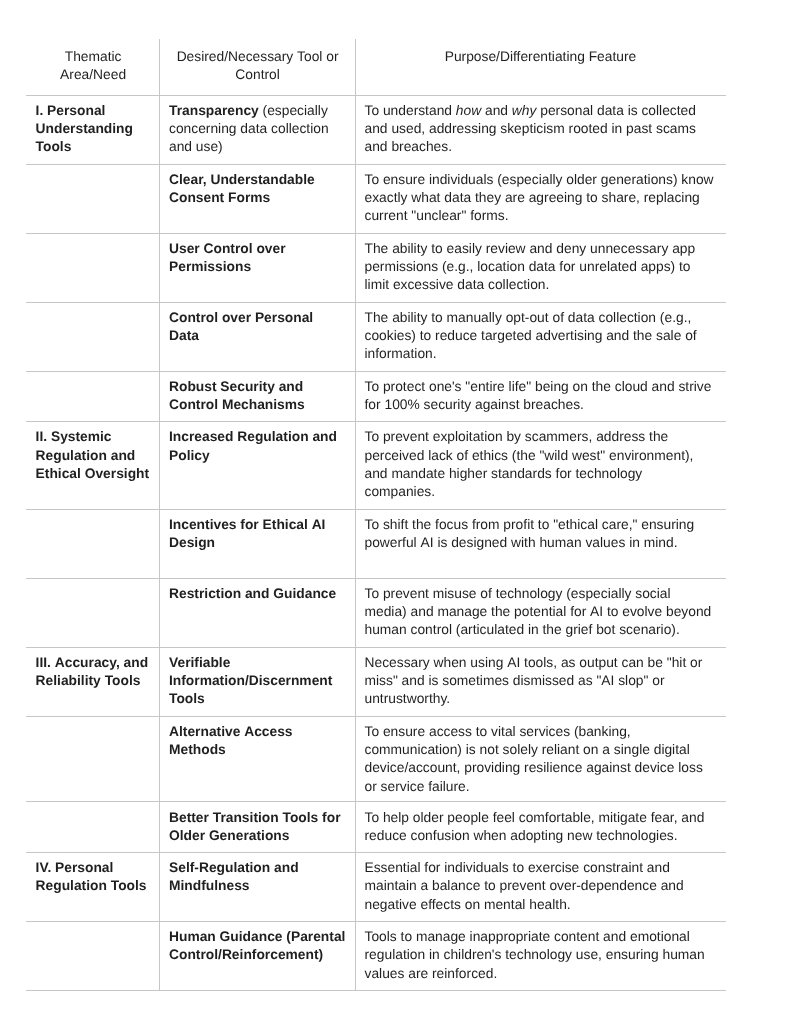

Below is a snapshot of some representative types of tools that were discussed throughout our project.

Mode of Consent

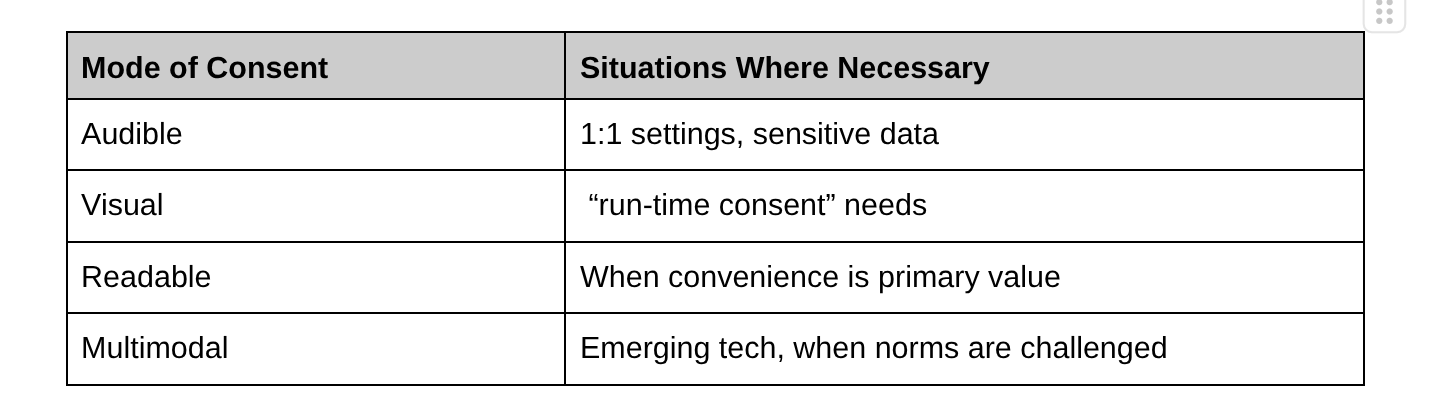

Mode of consent is also important, in our project we found that written consent was often not satisfactory and that sometimes participants desired a visual or verbal explanation before making a decision. The chart below shows the different types of consent desired in our project scenarios as well as the modes of consent desired.

Additionally based on our discussions the following seemed to be some general guidelines for when certain modes of consent were desired in certain situations:

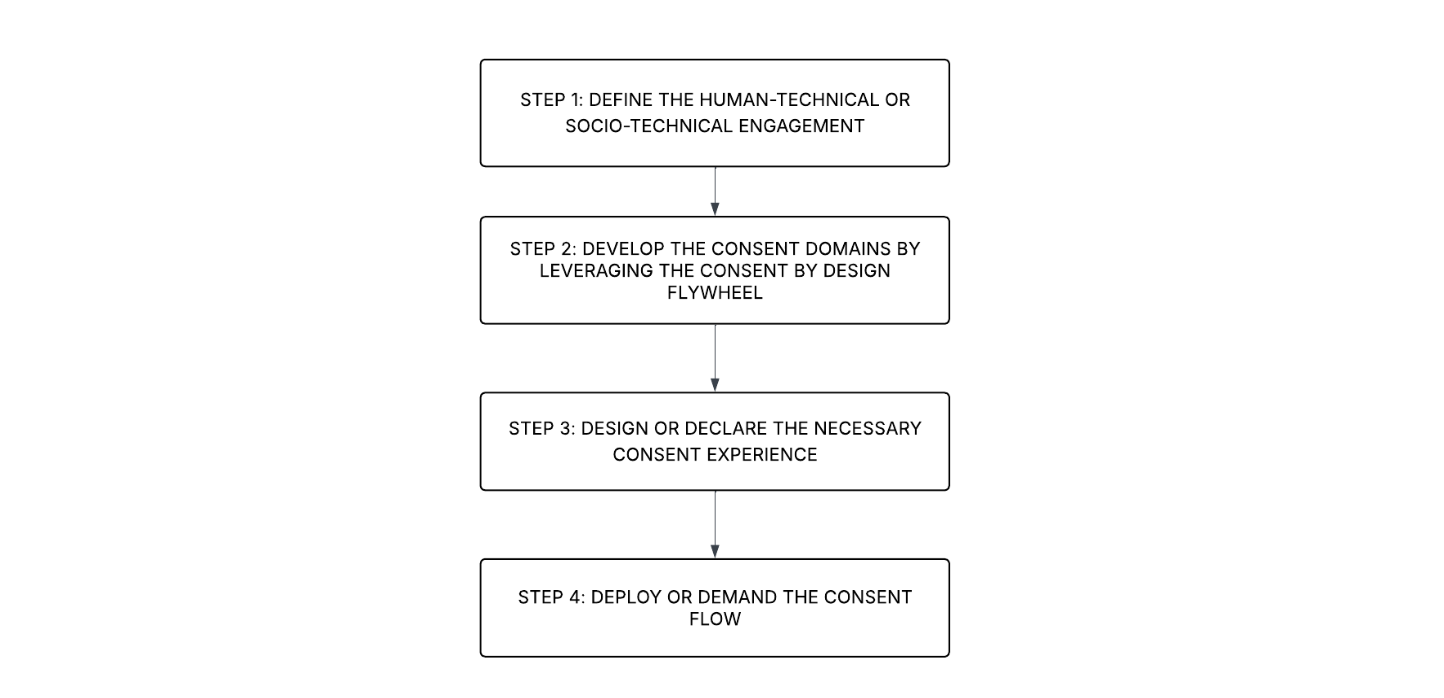

Examples of Framework Application

The contextual consent framework can be applied for a number of different cases - whether it be for communities, individuals, designers or law makers. A simple way to remember the framework is through the 4 D’s - DEFINE, DEVELOP, DESIGN and DEMAND (demand can also be replaced by either Declare or Decide). We will go through each step of the framework below and provide examples of how to apply these four steps based on your intended use.

-

This framework can be used by communities as a tool to provide structure around a socio-technical issue and articulate the specific needs of the community through the documentation and declaration of specific contextual values and perceived harms along with concrete and actionable solutions that can then be shared with law makers, advocacy groups or companies.

We encourage community leaders to use the framework in whatever ways works best for the community they are representing so the below applications are representative in nature and highly extensible.

DEFINE:

As a community, articulate the concern by defining the socio-technical engagement. Some examples of an articulated engagement based on our project are:

Our apartment building is getting a few upgrades. As part of the building upgrade - facial recognition technology is being installed at the front entrances of the apartment building.

Our place of worship is introducing an AI chatbot to answer questions on spirituality on the website

DEVELOP:

Determine the Baseline

It is important to understand the underlying ethical framework and background that your community holds. Your community may hold a unique set of backgrounds, values, life priorities, views on technology and experience so it is important to understand this and articulate those to set the baseline context for driving change within the socio-technical interaction in question. In our project, we distributed a survey to get a sense of the baseline values and views on technology that people held which helped frame the perspective participants were coming from, but as a community, you may already have a way of representing this or choose to define your baseline and background in a different way.

Dig Into Perspectives

Once you have this baseline, the next step is to get contextual input on the specific socio-technical situation being addressed. You can do this directly through a workshop, through a survey or through a series of 1:1 interviews. The most important part of this process is to understand the themes that arise across members of your community. We suggest leveraging the contextual consent flywheel as a guide to craft your questions. Below are a series of questions we asked during our project interviews that touched on many of the domains within the Contextual Consent Flywheel.

What assumptions are you making about the situation and the technology?

What are your expectations around the role and use of technology?

What values are most important to you to preserve?

What situations or outcomes would cause you to feel discomfort?

What would alleviate this discomfort?

Is there room for delegating/distributing decision making in this scenario, if so what does that look like?

Once you have sufficient feedback from your community, you can then work to distill your findings into the following themes:

Values

Potential Harms

Tools to Mitigate Harms

Decision Making Needs and Desires

Engage in Group Discussion

Prioritize themes

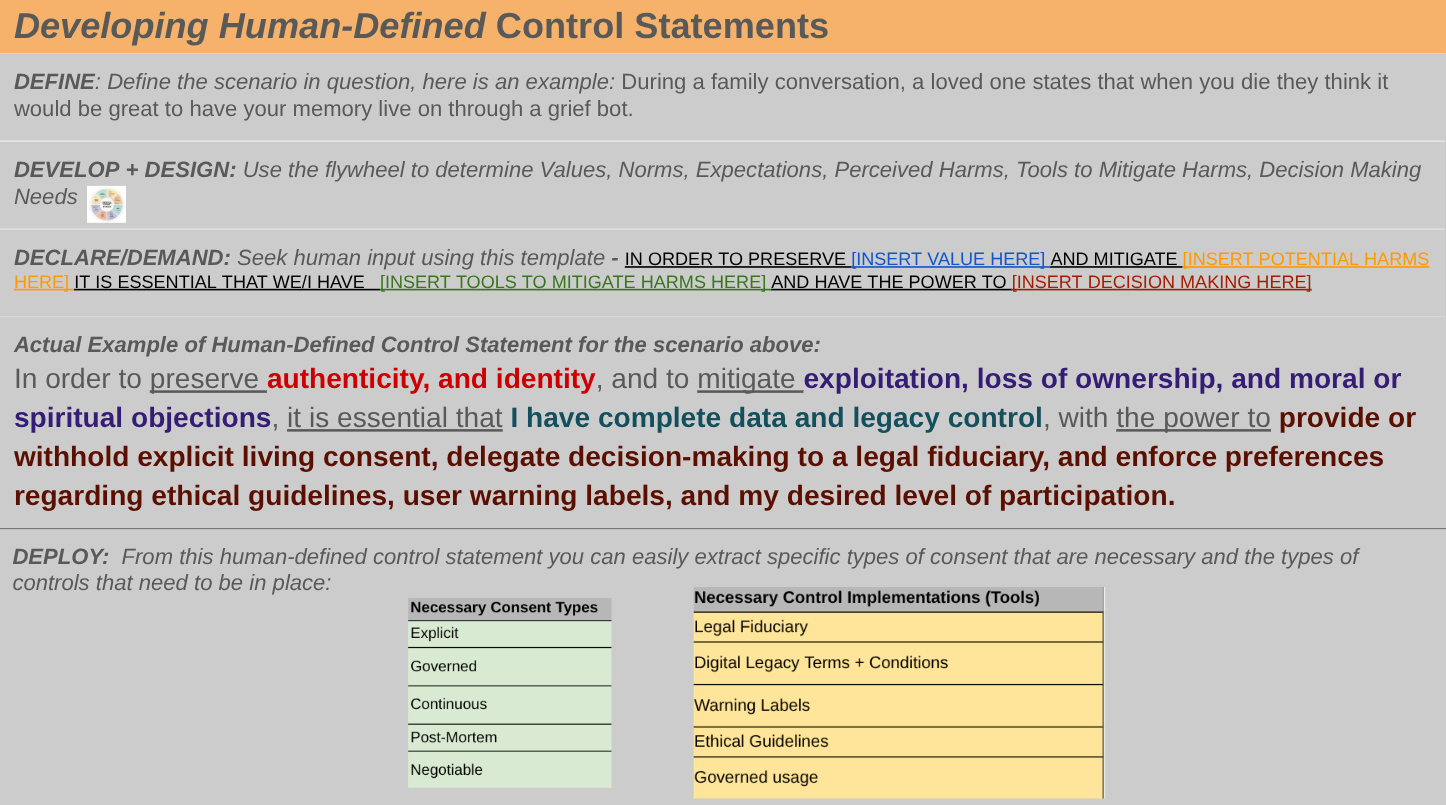

Develop individual and community control statements in the following format:

“IN ORDER TO PRESERVE [INSERT VALUE HERE] AND MITIGATE [INSERT POTENTIAL HARMS HERE] IT IS ESSENTIAL THAT I/WE HAVE [INSERT TOOLS TO MITIGATE HARMS HERE] AND HAVE THE POWER TO [INSERT DECISION MAKING HERE]”

DESIGN:

In this step you analyze your findings and work to distill the key themes from your engagements in order to design the necessary consent flow

DECLARE:

Share the top themes with lawmakers to advocate for change.

Share the control statements to provide actionable data that can drive immediate solutions

Consider aggregating the individual control statements into one consolidated control statement to help focus actionable change. Or consider working as a community to collectively develop a control statement based on active consensus.

-

This framework can be used by individuals who encounter a troubling or problematic human-technical interaction and are interested in taking action to change the nature or the terms of this human-technical interaction. It can be used as a spring board to work with others to seek action and change or can be used individually as a personal advocacy template.

DEFINE:

The first step is to reflect on the specific encounter or interaction that caused you concern. Think about how technology impacts that interaction. Some examples of an articulated interaction based on our project are:

My favorite shopping app now has an AI shopping agent feature that can provide recommendations and make purchases on my behalf, but in order to set it up, I need to scan my credit card and decide if I want to opt into personalization features so the agent can make more personalized recommendations.

I was playing a video game and a streamer hopped into the lobby and started streaming/recording while I was playing.

DEVELOP:

Define Your Baseline

Think about the underlying values that are relevant for this specific human-technical engagement. Think about how your background and values inform your opinion on how technology is being used in this situation.

Dig Into the Interaction

Once you have this baseline, the next step is to explore the specific contextual factors that made you stop to consider this interaction and explore ways of seeking more control and change. You can use the Contextual Consent Flywheel to systematically cover some of the elements that are relevant and/or you can think about the following to help structure your concern:

What assumptions are you making about the situation and the technology?

What are your expectations around the role and use of technology?

What values are most important to you to preserve?

What situations or outcomes would cause you to feel discomfort?

What would alleviate this discomfort?

Is there room for delegating/distributing decision making in this scenario, if so what does that look like?

Once you’ve had a chance to record some of these thoughts, work to group them into the following 4 buckets:

Norms - what norms are at play in the situation

Values - what values are at play in the situation

Expectations - what expectations do you have of the situation

Potential Harms - what are some of the potential harms you are concerned about in the situation

Tools to Mitigate Harms - what types of tools or controls do you want to feel more in control and to help mitigate some of your perceived harms?

DESIGN:

In this step you think through the types of controls you actually need to feel more comfortable - analyze your findings and work to distill the key themes. Develop your own control statement and think through the specific types and modes of consent you need.

DEMAND/DECLARE:Write a letter to the company or institution in question. Feel free to reach out and cite this page for any additional support you might want or need. Share with them your control statement and how the interaction in question prompted you to write by outlining the norms and values that were challenged as a result of the engagement.

-

This framework can be used by user experience designers and other individuals involved in the development and design of technology that may have a human-interaction component.

We highly recommend leveraging this framework earlier in the design process to ensure you can properly account for the consent needs and expectations of your user base.

DEFINE:

During the product design phase and/or when developing the product idea or requirements document or the product design document, consider what dynamics are in play with the technology that may include user decision making, user expectations, user values and any type of user perceived harm. Define the interaction.

Some examples of defining the interaction from a designer perspective are:

We are developing a new device called a “Magic Band” for the Recreation and Leisure Industry. This band will replace physical hotel keys and manual payment needs by allowing users to wear a digital device that is linked to their payment account and hotel account - thereby enabling frictionless experiences at resorts, amusement parks etc.

We are developing a digital grief bot - which will be an AI Avatar of a deceased human.

DEVELOP:

During the product design phase and/or when developing the product requirements document or the product design document, be sure to include a section on consent.

Consent is typically categorized as a subset of privacy which is often missing in design or requirements designs despite its utmost importance to ensuring trust and confidence from end-users.

Here are some sections you can include in your Privacy and/or Consent section when outlining your product requirements:

Consent Design Analysis

[Leverage the Consent Flywheel to address any or all of the key components of consent by design] - at a minimum be sure to include:

Likely User Norms

Anticipated User Expectations

Potential Perceived Harms or Risks

DESIGN:

The design phase can run in parallel to the develop phase and can be combined into a single document if necessary.

The Consent Design Analysis will inform the Consent Design Strategy.

Here is a suggested way to structure the Consent Design Strategy:

Consent Design Strategy

Types of Consent

Explain what types of consent will be used and provide a rational

Modes of Consent

Explain what modes of consent will be used and provide a rational

Consent Controls

Notices - explain what types of notices will be provided to cover transparency

Features - explain what features will be developed to ensure users stay in control

Settings - explain what other settings users will be provided to negotiate their level of consent.

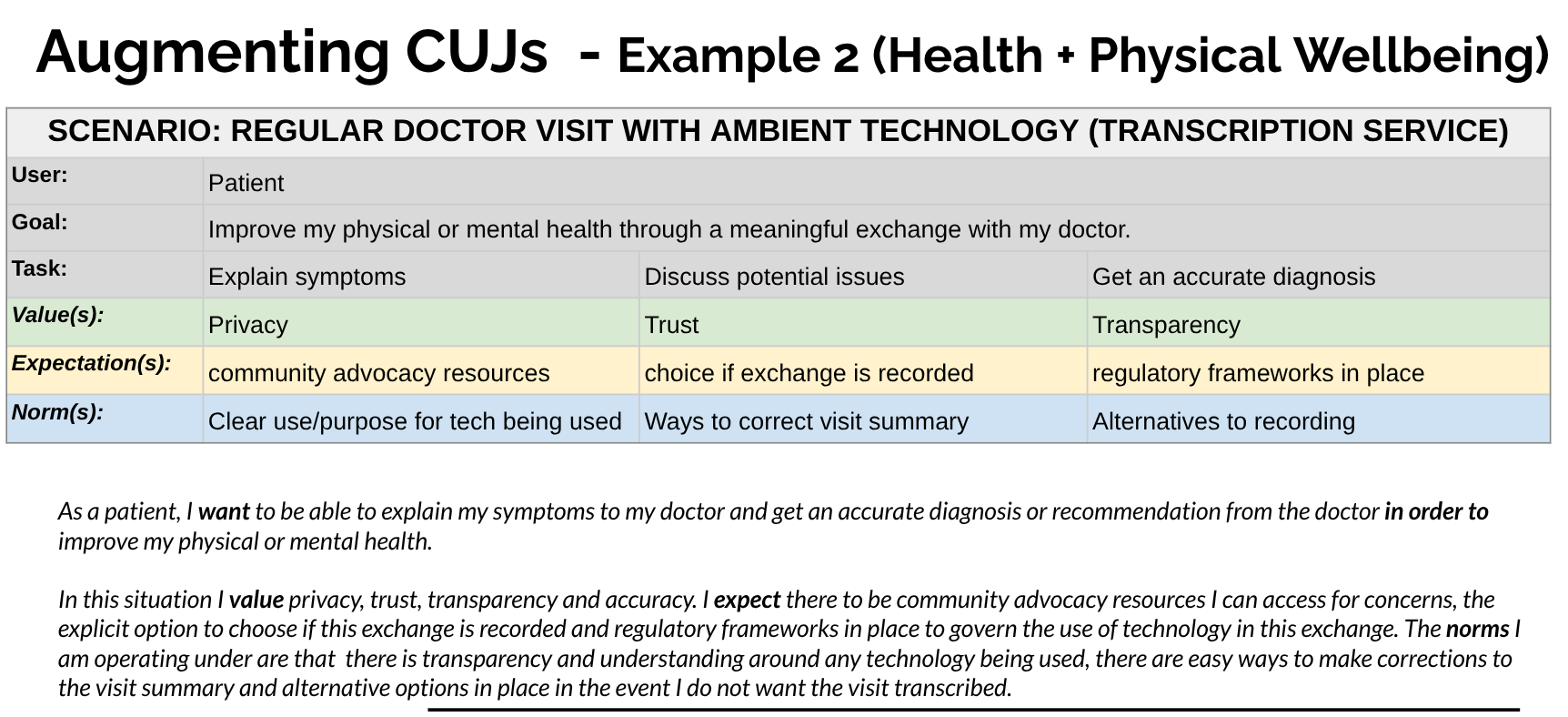

Additionally, when critical user journeys are being developed for a product, you can augment this process by incorporating consideration of user values, expectations and norms (VEN).

*See below for an example of using VEN to augment Critical User Journeys.

DECIDE:

There may be situations where it is not feasible to incorporate all consent requirements and you need to decide on the most critical components. If this is the case - be sure to key in on perceived harms of your user base and be sure you have adequate ways to mitigate these and also be sure you have a way for users to express concerns and voice feedback in a simple and direct way.

-

This framework can be used by tech leaders, innovation and strategy executives to inspire thoughtful technology development and implementation. It is essential that we have leaders who understand the importance of human control in technical environments and have frameworks and principles to guide strategies and roadmaps that balance profit, efficiency and automation with human values, expectations and norms.

We understand the ethical tensions that this type of work entails:

Consent is a loaded term and immediately puts people in a specific headspace

Consent for industry exists and is implemented to protect industry interests

Consent in tech is contractual - and is often performative by design

Consent regulation is expensive

Hard sell to “re-imagine” consent without a regulatory incentive

In spite of these tensions we encourage leaders to recognize the moment and the fundamental paradigm shifts that are emerging when it comes to technology-driven privacy and security tenants. This work can be leveraged in small sized chunks and any amount that is incorporated is one step in the right direction.

-

We hope regulators and law makers consult this framework to drive regulatory change. Technology is moving fast and we need enduring frameworks and principles that can withstand the rapid pace of technological advancement. This framework can endure in this environment and was born during the season of rapid technological transformation across the world.

Here are few ways we encourage regulators and law makers to use our framework:

Reference this website and/or this toolkit when drafting new regulation around privacy, consent and consumer protection

Use the human-derived control statements (see resource below) as a basis for rethinking how we mandate controls be implemented when it comes to consent and control.

Expand the scope of privacy and security regulation beyond personal data given that the boundaries between humans and technology are becoming more and more complex - necessitating more than just data threat models.